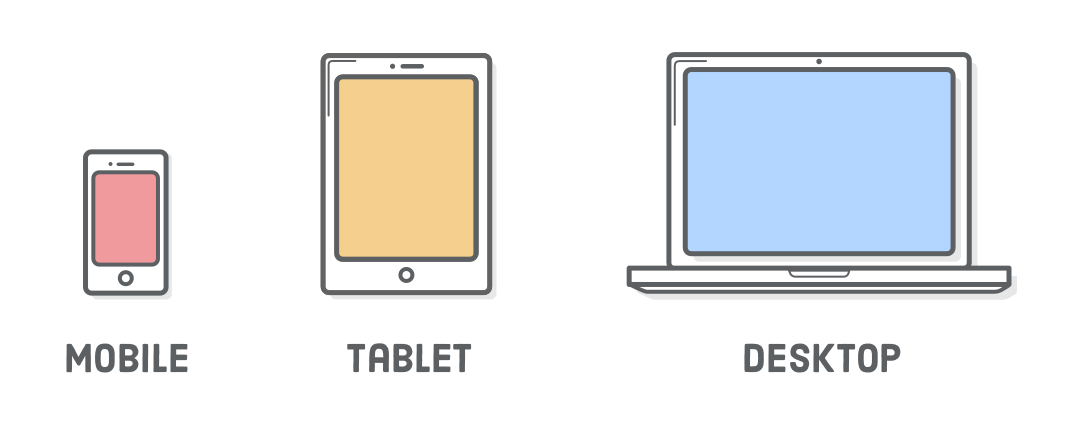

“Responsive design” refers to the idea that your website should display equally well in everything from widescreen monitors to mobile phones. It’s an approach to web design and development that eliminates the distinction between the mobile-friendly version of your website and its desktop counterpart. With responsive design, they’re the same thing.

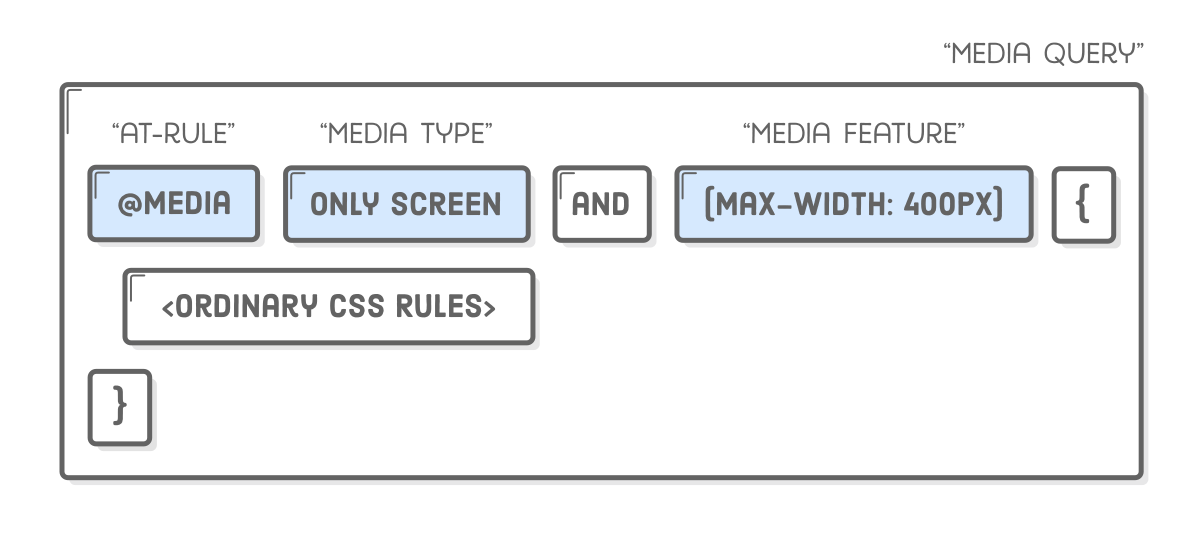

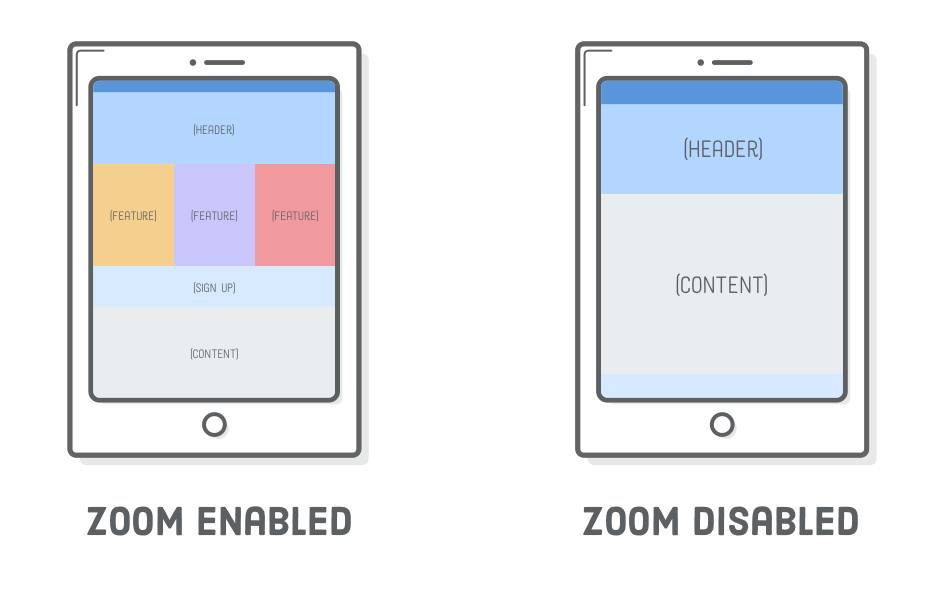

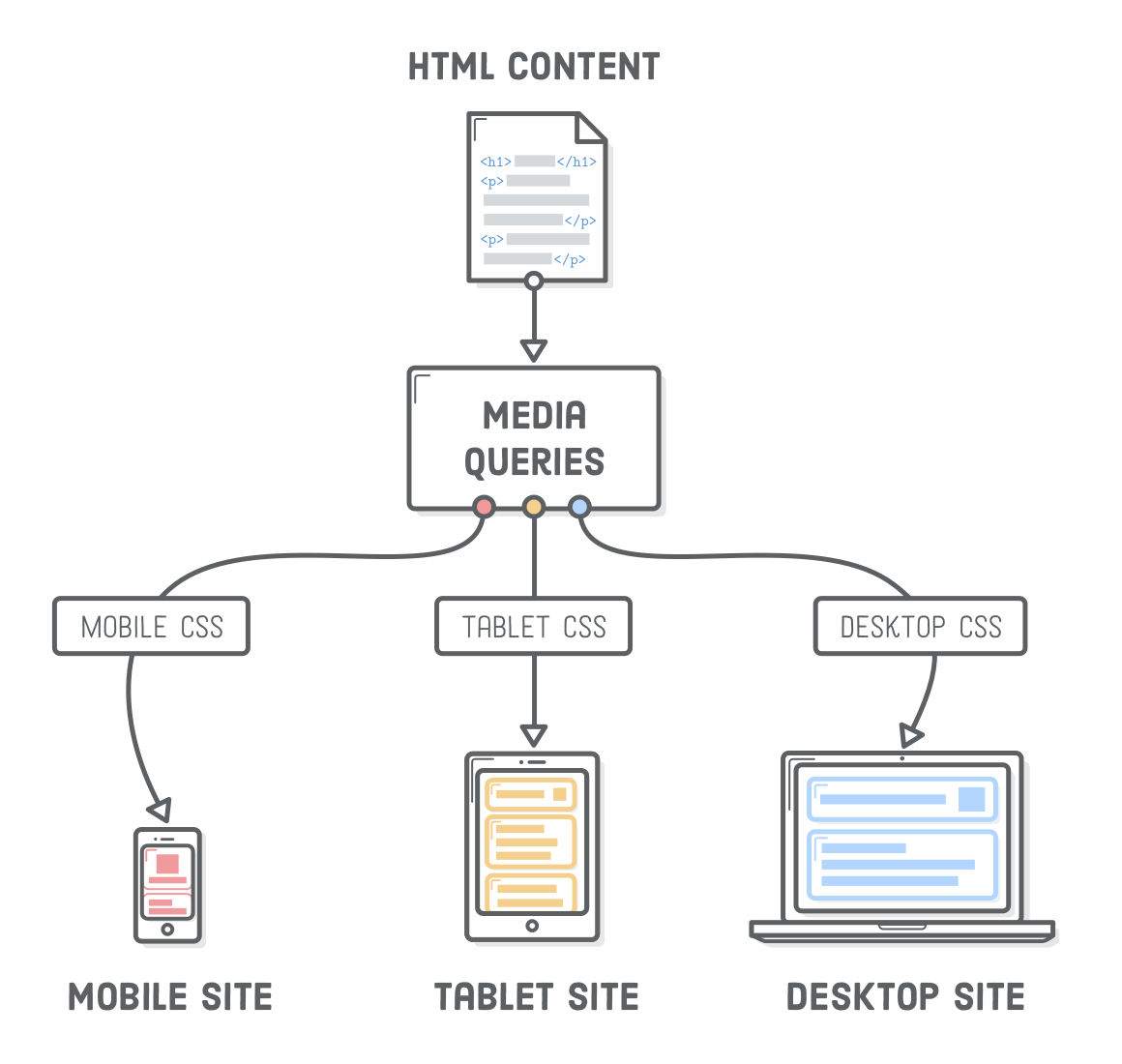

Responsive design is accomplished through CSS “media queries”. Think of media queries as a way to conditionally apply CSS rules. They tell the browser that it should ignore or apply certain rules depending on the user’s device.

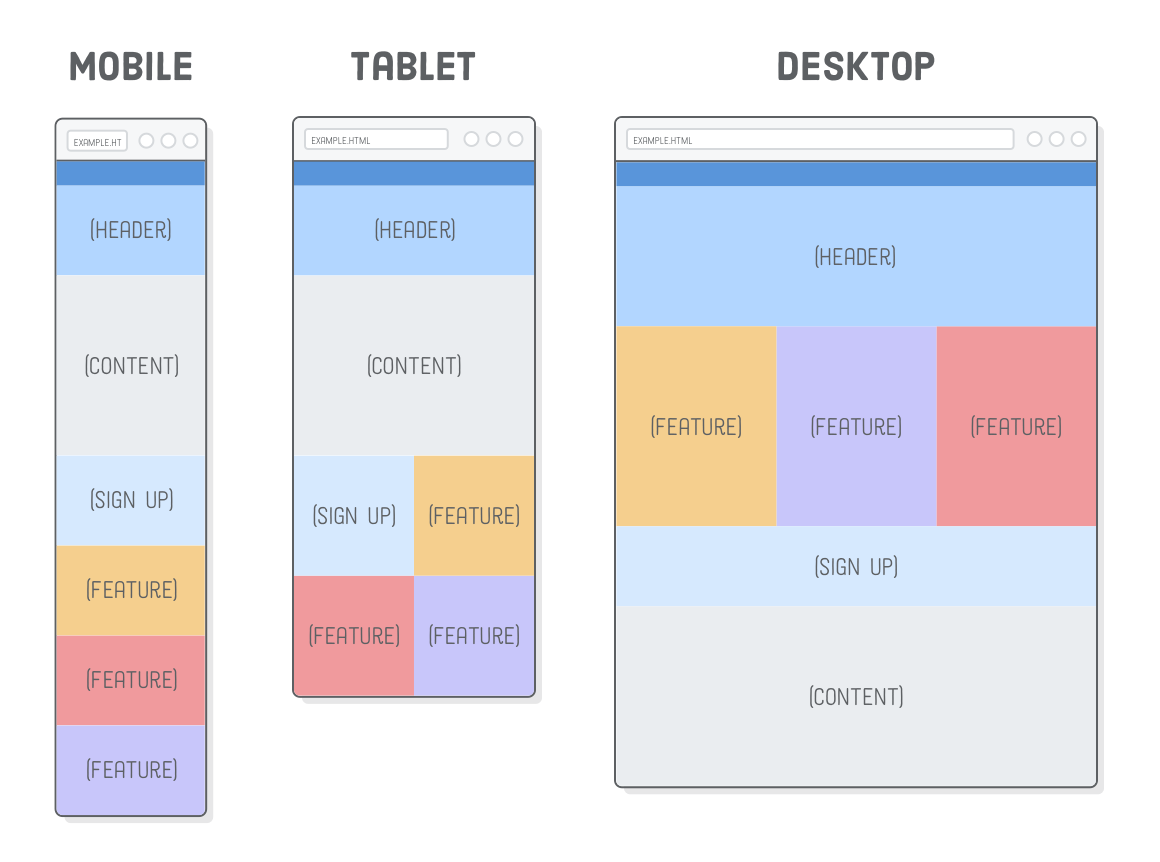

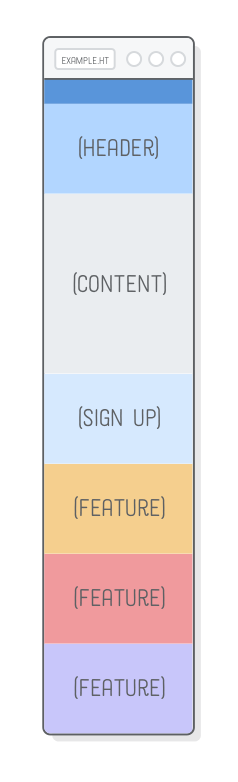

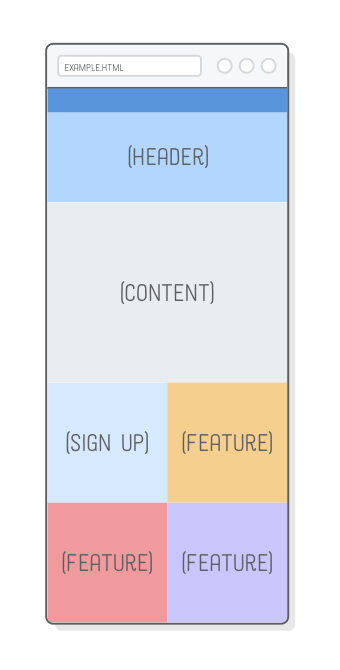

Media queries let us present the same HTML content as distinct CSS layouts. So, instead of maintaining one website for smartphones and an entirely unrelated site for laptops/desktops, we can use the same HTML markup (and web server) for both of them. This means that whenever we add a new article or edit a typo in our HTML, those changes are automatically reflected in both mobile and widescreen layouts. This is the reason why we separate content from presentation.

In this chapter, we’ll learn how media queries are really just a thin wrapper around the plain old CSS that we’ve been working with up ’til this point. As we’ll soon discover, it’s actually pretty easy to implement a responsive layout. (Responsive Images, on the other hand, are an entirely different story).